Part 1: Introduction and context

On this page

‘Granny flat’ is a common term to describe a small, self-contained house. These are also known as secondary or ancillary dwellings, family flats, minor dwellings, self-contained small dwellings and minor residential units.

The Government has committed to ‘amend the Building Act and the resource consent system to make it easier to build granny flats or other small structures up to 60 square metres, requiring only an engineer's report’.[1] This discussion document presents options for achieving the Government’s commitment, through potential changes to the Building Act 2004 (Building Act) and the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA).

The Government is progressing a wider package of work to streamline the building consent process[2] and address the housing crisis. The package includes the ‘Going for Housing Growth’ policy[3] and their 100-point plan to rebuild the economy.[4] The policy to enable granny flats will support broader outcomes for housing.

Problem definition – what we want to address

Housing affordability is a key issue in New Zealand

New Zealand has some of the least affordable housing in the world[5] and home ownership dropped from 74% in the 1990s to 65% in 2018.[6] Over the 12 months to June 2023, average housing costs per week increased 14.5%. Data from 2023 illustrates that over a quarter of households that do not own their home now spend more than 40% of their income on housing.[7] High housing costs have a greater impact on retirees on fixed incomes, Māori, Pacific people, and people with disabilities.

There is increasing demand and a lack of supply of small houses

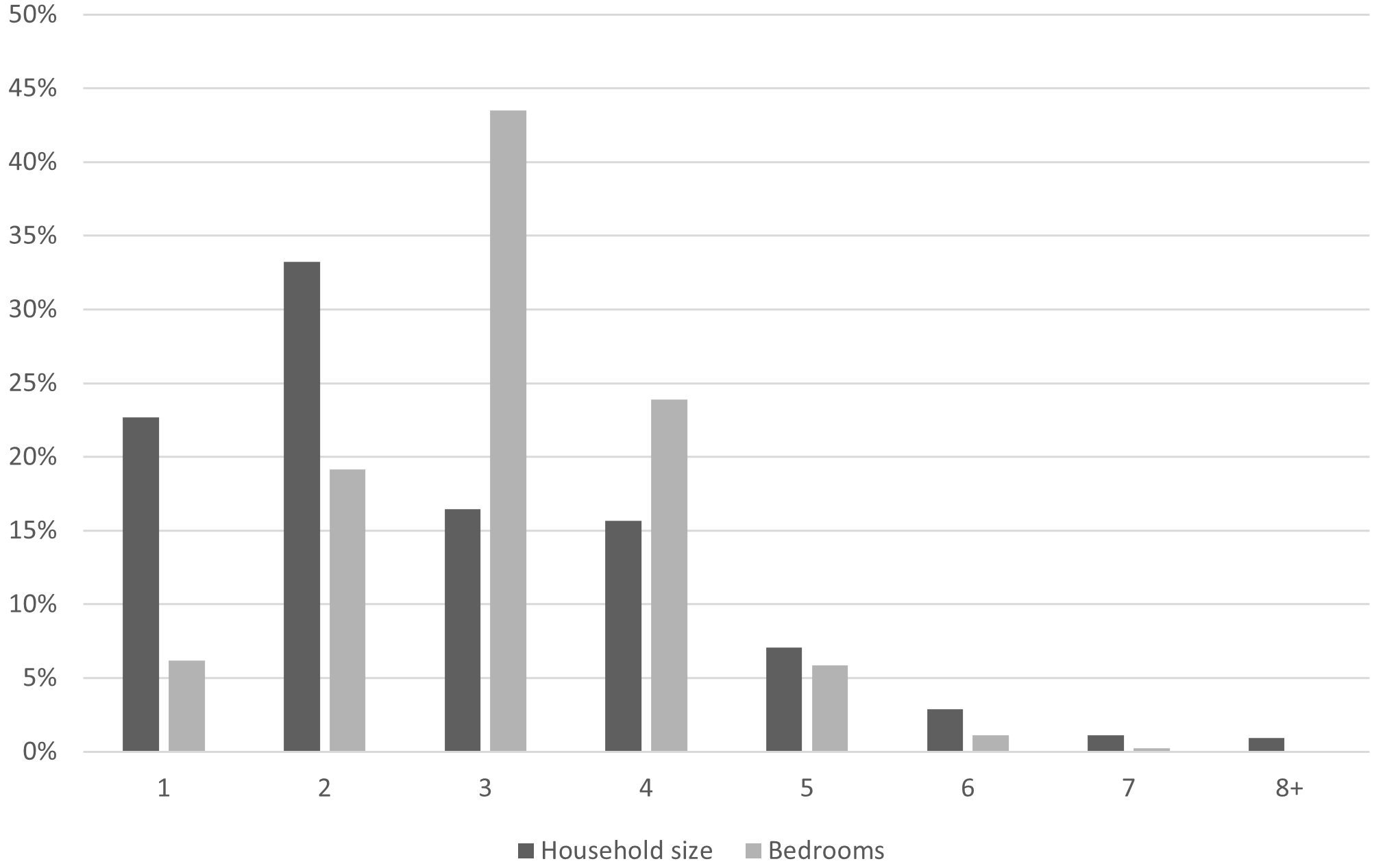

In 2018, just under 20% of houses in New Zealand had 2 bedrooms with 6% having 1 bedroom. In contrast, more than half of households had 1 or 2 people.[8] Demographic changes such as an increase in single parent families, people having fewer children and an ageing population are likely to increase the demand for smaller houses in the future.

Household size and number of bedrooms

View chart description and data

Regulatory barriers increase the time and cost to build new houses and processes should be proportionate to the risks

Housing has become more difficult and expensive to build in New Zealand. The cost of building a house increased by 41% since 2019.[9]

Regulatory compliance costs for consenting and building are part of what drives housing costs. Building consent fees for a small house are estimated to be around $2,000-5,000.[10] Where a resource consent is required for a small house, it is estimated to cost around $1,500.[11]

Homes consented in the June 2022 quarter took, on average, over 16 months to reach their final inspection (up from over 14 months in the June 2021 quarter) and a further 2 months to receive a code compliance certificate.[12]

This has an impact on the number of small houses being built. If costs and processes were less, more smaller houses would likely be built. If more are built, unmet demand would reduce and the cost of housing would likely decrease.

Question 1: Have we correctly defined the problem? Are there other problems that make it hard to build a granny flat?

Outcome and principles – what we want to achieve

The intended outcome of this policy is to increase the supply of small houses for all New Zealanders, creating more affordable housing options and choice.

While these houses can be referred to as ‘granny flats’, the proposals are not limited to older New Zealanders or family members.

The principles for achieving this outcome include:

- enabling granny flats and other structures in the resource management and building systems, with appropriate safeguards for key risks and effects

- coordinating requirements in the resource management and building systems, where appropriate

- supporting local government funding and infrastructure by ensuring growth pays for growth

- supporting intergenerational living and ageing in place.[13]

Question 2: Do you agree with the proposed outcome and principles? Are there other outcomes this policy should achieve?

Legislative context – what can you do now

Housing in New Zealand is largely regulated by 2 pieces of legislation:

- the Building Act 2004 (Building Act) – sets the rules for the construction, alteration, and demolition of new and existing buildings

- the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) – sets requirements for the management of land use and effects on the environment.

Development may require both a building consent and resource consent, depending on the context. Although they manage different risks and effects, the Building Act and the RMA collectively determine which rules a development is subject to.

The Building Act 2004

The Building Act aims to ensure homes and buildings are safe, healthy and durable.

Currently, to build a standalone dwelling up to 60 square metres, the design and building work must go through the building consent process and any restricted building work must be done or supervised by a Licensed Building Practitioner.

Building consent authorities (BCAs) must check building consent applications for compliance with the Building Code before work can begin. During construction, BCAs will inspect the work to ensure it is in accordance with the building consent. When the building work is complete the owner applies for a code compliance certificate and the BCA will issue one if the building complies with the building consent. These steps add time and cost, but they give building owners, tenants, banks and insurers confidence in the quality and function of the house.

Carrying out building work without a building consent when one is required is an offence under the Building Act, with significant fines of up to $200,000 on conviction and an infringement fee of $1,000.

Fast tracked building consent options under the Building Act 2004

There are fast track paths for building a dwelling of 60 square metres or less:

- BCAs must accept a MultiProof approved design,[14] and opportunities for costly delays are limited.[15]

- Offsite manufacturers certified under the BuiltReady[16] scheme can issue their own certificates for a component or building. These certificates must be accepted by BCAs as part of the building consent process

Building work that does not require a building consent

The Building Act specifies certain building work that is low-risk, such as certain garages and sleepouts, is exempt from building consent requirements. These exemptions are found in Schedule 1 of the Building Act, and recognise the disproportionate cost of the full building consent process for this work. Under Schedule 1, councils can also use their discretion to give an exemption where they consider that a building consent is not necessary.

Some building consent exemptions in Schedule 1 require the use of a Licensed Building Practitioner, a person authorised under the Plumbers, Gasfitters and Drainlayers Act 2006 or a Chartered Professional Engineer.

All building work must comply with the Building Code and BCAs can issue a Notice to Fix if it does not. This includes consented, unconsented, and consent-exempt work.

Consumer protections under the Building Act

The Building Act includes a range of protections for consumers in relation to residential building work. These include requirements for written contracts for work over $30,000, a set of implied warranties that run for up to 10 years and a 12-month defect repair period. In some cases, builders may offer their own third-party surety to attract customers. Examples include the Master Build Guarantee by Master Builders and the Halo Guarantee by NZ Certified Builders.

The Resource Management Act 1991

Under the RMA, councils must develop a district plan and regional plan.[17] District plans are the rulebook for how you can use and develop land. Regional plans set out rules that manage the taking of water, the discharge of contaminants, earthworks and activities in the coastal marine area. These plans tell you what you can or cannot do, and if you need a resource consent.

Most district plans currently allow granny flats and other structures under 60 square metres in residential and rural zones without needing resource consent, if it meets certain permitted activity standards.[18] These standards might include building position, building height and building size and they vary across different district plans. If a granny flat doesn’t meet the permitted activity standards in the district plan it will need a resource consent.

Regional plans don’t have specific requirements for granny flats but may require a resource consent in certain circumstances, such as for on-site wastewater systems.

National direction under the RMA supports local decision-making and can set requirements for district and regional plans. Appendix 2 outlines the purpose and scope of national direction tools in further detail.

Further information on the RMA is available on the Ministry for the Environment website:

Understanding the RMA and how to get involved(external link) — Ministry for the Environment

Safeguards – what risks need to be managed

There are risks that have been considered through the development of the policy to enable granny flats and other structures across the resource management and building systems, including:

- Building safety and performance – if building work does not meet minimum standards, there are significant risks to the health and safety of people using the building and risks of property damage. Building failure could include structural collapse, weathertightness issues that create leaky buildings, fire and inadequate plumbing work that creates public health issues. The costs of building failure can be significant and may impact a third party, such as a tenant or neighbour.

- Trust in building quality – if buyers, tenants, insurers and mortgage lenders are not confident that a granny flat will be built to a high standard without regulatory oversight it may be challenging to sell, let, insure or finance them.

- Environmental effects – overriding rules and standards in RMA plans could impact privacy, create environmental effects and have other unintended consequences.

- Infrastructure planning – enabling granny flats will put increased demand on council infrastructure including drinking water, wastewater, stormwater, roading and community facilities. Councils need to know when new homes are built so they can increase infrastructure systems and services and plan for the future.

- Infrastructure funding – development contributions are charges that ensure that the costs associated with providing infrastructure and services for new residents is funded by the new residents (or the developer who created the new homes) rather than by the existing residents. Development contributions are currently triggered by a building consent, resource consent or when a new house is approved to connect to council infrastructure. If consents are not needed and infrastructure connections are not recorded, these contributions may not happen.

- Rating/property information – when new homes are built a record is created by the council. This record is important as it enables councils to update their rates records, manage infrastructure services, plan to address any risks from natural hazards, maintain accurate property records to report to government agencies and provide accurate Land Information Memorandums (LIMs).

The proposals outlined on the next page aim to mitigate these risks.

Question 3: Do you agree with the risks identified? Are there are other risks that need to be considered?

Footnotes

[1] National and New Zealand First Coalition Agreement: page 9.

[2] Streamlining Building Consent Changes(external link) — Beehive.govt.nz

Building products shakeup to lower prices(external link) — Beehive.govt.nz

[3] Speech to the Wellington Chamber of Commerce(external link) — Beehive.govt.nz

[4] National’s 100-point plan to rebuild the economy(external link) — National

[5] OECD (2020) How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being. OECD Publishing, Paris.

[6] Statistics New Zealand (2020) Census data from Housing in Aotearoa.

[7] Household income and housing-cost statistics: Year ended June 2023(external link) — Statistics New Zealand

[8] Statistics New Zealand (2018) Census data.

[9] The 41.3% represents the cumulative increase since the fourth quarter of 2019. This mostly occurred in 2021 and 2022.

[10] In a 2022 report Does size matter? The impact of local government structure on cost efficiency, the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission estimated the median fee to process a building consent for a $350,000 new build residential dwelling at $3,780, but also noted that there was considerable variation in costs between councils (standard deviation: $1,540). Note that the Building Levy ($1.75 (incl. GST) per $1,000 of building work at $20,444 (incl. GST) and over) and BRANZ Levy ($1.00 per $1,000 of the total value of construction work at $20,000 and over) also attach to building consents (rates as at June 2024).

[11] National Monitoring System 2021/22 consent data for minor residential units.

[12] Experimental indicators show longer building timeframes(external link) — Stats NZ

[13] Ageing in place describes people having housing choices in their local area throughout their lifetime, so they do not have to leave the area to access a specific type of housing.

[14] MultiProof is a statement by MBIE that a set of plans and specifications for a building complies with the Building code. A building consent application that includes a MultiProof receives a fast-tracked consenting process (BCAs must grant or refuse it within 10 working days instead of the usual 20).

[15] There are several relevant approvals on the MultiProof register for dwellings of 60 square metres or less.

MultiProof register(external link) — Building Performance

[16] About BuiltReady(external link) — Building Performance

[17] Some councils integrate these plans into a single document (eg, the Auckland Unitary Plan).

[18] ‘Standards’ are the requirements, conditions and permissions that that an activity must comply with to be deemed permitted and not require a resource consent under RMA section 87A (1).