Permitted activity standards and alignment with district plans

On this page

What was proposed

Six permitted activity standards were proposed to control the bulk and location of buildings. The proposed standards were informed by an analysis of existing district plan provisions for granny flats.

Questions 21 and 22

What was asked

Question 21: Do you agree or disagree with the recommended permitted activity standards? Please specify if there are any standards you have specific feedback on.

Question 22: Are there any additional matters that should be managed by a permitted activity standard?

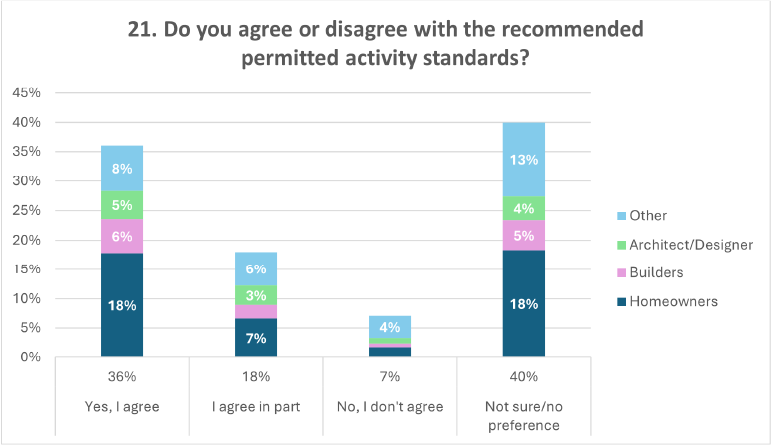

Figure 15: Graph detailing the response to question 21

Figure 15: Graph detailing the response to question 21

Summary of feedback

In response to question 21, 1450 submitters responded to this question and 267 submitters provided a further explanation of their view. In response to question 22, 192 submitters responded.

The responses to these questions were varied and raised a wide range of additional matters to consider for the permitted activity standards.

Key themes

Confusion between the conditions under the Building Act proposal and the permitted activity standards under the Resource Management Act proposal was a key theme amongst all submitter types. Submitters considered there needs to be consistency across the two systems.

Another key theme was that existing district plan rules should apply in place of all or some of the proposed permitted activity standards. Submitters considered some matters are better managed at a local level and a national standard would not provide for local contexts and issues. Submitters were also concerned that the standards may add another layer of complexity and increase implementation issues.

Feedback on each of the standards was varied across all demographic groups, however there was some consensus on the most appropriate options. The feedback received on each of the proposed permitted activity standards is summarised in Table 2, below.

Table 2: Summary of feedback received on each standard and recommended additional standards

| Proposed permitted activity standard | Summary of submissions |

|---|---|

|

Internal floor area: Maximum 60 square metres, measured to the inside of the enclosing walls or posts/columns. |

Many homeowners considered the maximum internal floor area standard should be increased, to as much as 100 square metres. A few councils questioned why this size was chosen, as it is not representative of what is already permitted under district plans (most district plans that permit granny flats enable these up to 60-100 square metres). Many submitters considered more than one minor residential unit should be permitted per site, especially on rural sites, and some considered this would better support Māori housing outcomes. |

|

Number of granny flats per site: One granny flat per principal residential unit on the same site. |

Many submitters considered more than one minor residential unit should be permitted per site, especially on rural sites, and some considered this would better support Māori housing outcomes. |

|

Relationship to the principal residential unit: The minor residential unit is held in common ownership with a principal residential unit on the same site (as defined in the National Planning Standards). |

Many submitters, especially homeowners, and iwi, hapū and Māori considered this definition would be a barrier to the policy and not provide for tiny homes, renters, or Māori ownership on whenua Māori (Māori land) with multiple owners. |

|

Building coverage: The options for maximum building coverage for granny flats and principal residential units collectively are:

|

Most submitters, especially councils, provided feedback that existing district plan rules should apply. The most popular of the proposed options was option a – 50%, especially since it aligns with the medium density residential standards. Concerns were raised about stormwater and flooding and that these building coverage options are too high, especially in smaller council areas. Lower maximum building coverage of 45% or 40% were recommended. There was some support for no maximum building coverage in rural zones. Concern was raised by councils and some architects about how the building coverage standard would interact with building coverage standards for the principal dwelling. |

|

Permeable surface: The options for minimum permeable surface are:

|

There was more support for option b – 30%, however some submitters considered either option a or b is appropriate. Some submitters considered the standard should be greater, particularly due to flooding concerns. |

|

Setbacks: The options for minimum setbacks in residential zones are:

The options for minimum setbacks in rural zones are:

|

Many submitters considered existing district plan rules should apply and that setbacks should align with the height to boundary condition outlined on page 10 of the discussion document. Submitters sought specific setbacks from state highways, railway lines, transmission lines and primary production activities. Residential: in residential zones, submitters mostly preferred options a and b. Some submitters suggested even greater setbacks, while others preferred option c: having no setbacks. Rural: responses were very mixed on rural zones. There was slightly more support for option a or a middle ground between the two options. However, a few councils considered it should be greater than both options. There was a mixture of support and opposition for a maximum distance between principal dwellings and granny flats. |

|

Building height and height in relation to boundary: No building height and height in relation to boundary standards are proposed. This is because the policy intent is to enable single storey granny flats and existing building height and height in relation to boundary setbacks in underlying zones will already enable this. |

There was a mixture of support and opposition for including standards for height and height in relation to boundary in the national environmental standard. Some submitters considered it is confusing to have a standard under the Building Act proposal but not the Resource Management Act proposal. |

|

Additional matters that should be addressed by the National Environmental Standards |

Many submitters considered additional standards should be included in the national environmental standard. These include:

|

Sector views

Homeowners

Most homeowners considered more than one minor residential unit should be permitted per site and that the internal floor area standard should be larger. Many homeowners considered the policy being limited to properties with an existing home on it and the requirement for the granny flat to be held in common ownership with the primary dwelling are barriers to this policy.

Iwi, hapū and Māori

Iwi, hapū and Māori have raised issues about the definition for ‘minor residential unit’ not providing for Māori ownership where there are multiple owners. Concerns were also raised that the policy should not limit the number of granny flats to one per principal dwelling on a site.

Councils

Some councils have raised concerns with specific implementation and interpretation issues with some of the standards. On building coverage, concern was raised about how this standard would interact with existing building coverage standards for other activities, such as dwellings.

Concern was raised about how councils would manage minor residential units that are larger than 60 square metres. Some councils considered the definition should include a 60 square metres limit, so any larger granny flats would need to comply with other relevant standards and not those set out in the national environmental standard.

A general concern raised was that the standards would impact the permitted baseline [1]. This would have a significant impact, especially in tier 2 and 3 council areas,[2] by increasing the expected level of development on a site.

If combined primary dwelling and MRU coverage is permitted at 50%, the permitted baseline for habitable buildings would become 50%. This would alter the character of these zones substantially and far beyond the effect of any MRU (Christchurch City Council).

Industry

Builders, architects/designers and planners

Many builders, some architects/designers and a few planners considered more dwellings per site is appropriate, especially on larger rural sites. Some builders, architects/designers and planners considered existing district plan rules should apply, and the proposed standards add another layer of complexity.

Industry/professional organisations

Auckland Property Investors considered the most enabling residential setbacks, building coverage, and permeable surface options are appropriate. However, NZ Certified Builders association considered the lowest site coverage 50% to be best.

There was support from Horticulture NZ and the Pork Industry Board to have no maximum building coverage or minimum permeable surface in rural zones. Taituarā considered there should be a maximum distance from the principal dwelling to the granny flat in rural zones.

Taituarā noted the proposal would lead to mismatching between the standards in the national environmental standards and existing district plan standards. There was concern from New Zealand Planning Institute and Architectural Designers NZ that the standards in the national environmental standards are unnecessary and add complexity.

Advocacy groups

Disabled Persons Assembly NZ considered there needs to be a standard requiring granny flats to meet Lifemark universal design standards. Disability Connect Incorporated was concerned that the internal floor area requirement is not large enough to enable granny flats to be accessible.

There was concern from Waiheke Community Housing Trust and Community Networks Aotearoa that the building coverage and permeable surface requirements are unsuitable on Waiheke on sites with on-site wastewater and stormwater servicing.

Herne Bay Residents Association and the Character Coalition Incorporated raised concerns that granny flats could negatively impact character and heritage.

Infrastructure providers

KiwiRail, Orion and PowerCo considered there should be additional setback requirements from rail corridors and overhead electricity lines. KiwiRail also sought acoustic standards to reduce reverse sensitivity on their operations. Transpower noted a standard should be added to the national environmental standards that precludes granny flats from being located within the National Grid Yard.

Invercargill Airport, Auckland Airport and NZ Airports Association submitted that the national environmental standards must not override existing council provisions that protect nationally and regionally significant infrastructure, including matters related to aircraft noise.

Question 23

What was asked

Question 23: For developments that do not meet one or more of the permitted activity standards, should a restricted discretionary resource consent be required, or should the existing district plan provisions apply? Are there other ways to manage developments that do not meet the permitted activity standards?

Summary of feedback

In response to question 23, 399 submissions were received. There was a relatively equal split between submitters that consider a restricted discretionary resource consent is appropriate and submitters that considered existing district plan rules should apply. Homeowners, Iwi, hapū and Māori and most councils generally considered existing district plan provisions should apply. There was slightly more support from industry submitters for restricted discretionary resource consents.

Key themes

A common theme raised by submitters, especially homeowners, was developments that do not meet the permitted activity standards should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis.

Of the submissions in support of existing district plan rules applying, a key theme raised was that resource consents are costly, and it defeats the purpose of this policy if a resource consent is required.

Conversely, another key theme was the national environmental standards will better achieve nationwide consistency if it specifies a restricted discretionary resource consent is required and if it sets specific matters of discretion[3].

Sector views

Homeowners

There was slightly more support from homeowners that existing district plan rules should apply.

There was some concern that the resource management approach adds to the complexity of the policy and should be kept as simple as possible.

Some submitters considered that where a development does not meet one of more of the standards, it should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. Either a resource consent should be required, or the existing district plan rules should apply depending on what is more appropriate.

Iwi, Hapū and Māori

Iwi, hapū and Māori raised concerns about how expensive and time-consuming consents are and that existing district plan rules should apply for developments that do not meet the standards.

Councils

Generally, councils supported that existing district plan provisions should apply. This is because district plan provisions have been designed to manage local issues, including natural hazards and these may not be considered by a resource consent under the national environmental standard.

A few councils considered that requiring a restricted discretionary resource consent for developments that do not meet one or more of the proposed standards is more appropriate. This approach would better achieve consistency across different councils, and this is a neater approach. Councils considered if the national environmental standards specify a restricted discretionary resource consent is required, the matters of discretion should enable councils to address all relevant issues.

"If a NES is to be used, Council believes it would be neater if the NES was a one-stop shop and included a restricted discretionary resource consent pathway. Otherwise, councils will probably need a plan change to create the right fit – knitting the two could be complicated and add costs to council (Kāpiti Coast District Council). "

Industry

Developers, builders, architect/designers, planners

There was support for both approaches, however there was slightly more support for a discretionary resource consent from developers, builders, architect/designers and planners.

Some industry submitters, especially architect/designers and builders questioned why a restricted discretionary resource consent is specified and not other activity statuses including a controlled activity or a discretionary activity.

Infrastructure providers

Kiwirail considered a restricted discretionary activity is not appropriate for developments that breach the internal floor area, number of granny flats per site and the relationship to the principal unit standards. This is because these three standards are fundamental to the granny flat definition.

Transpower New Zealand Limited submitted that a non-complying activity status should be required where a granny flat is in the National Grid Yard.

Notes

[1] Sections 95D(b) and 95E(2)(a) of the RMA provide that when determining the extent of the adverse effects of an activity or the effects on a person respectively, a council ‘may disregard an adverse effect if a rule or national environmental standard permits an activity with that effect’ (Quality Planning)

[2] National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2020. Page 31. Ministry for the Environment(external link)

[3] The matters a council can consider when determining whether to decline a resource consent or to grant it and impose conditions.