Chapter 3: Anti-competitive conduct

On this page

Anti-competitive conduct in the Commerce Act

Part 2 of the Commerce Act prohibits certain types of anti-competitive conduct by firms, whether that be single firms acting alone, or multiple firms forming illegal agreements. These provisions help protect consumers from the costs and harm associated with behaviour that limits competition in markets. In particular:

- Section 27 prohibits agreements that have the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

- Section 28 prohibits covenants relating to land that have the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

- Section 30 prohibits cartel conduct, which involves agreements or covenants among competitors that contain price fixing, market allocation or output restriction clauses.

- Section 36 makes it illegal for a business with a substantial degree of market power to engage in conduct that has the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in any market.

In the event of an anti-competitive agreement or conduct which may provide a benefit to the public, the Commission can provide authorisation if it is satisfied that the benefit outweighs the lessening of competition. In addition, it can give clearance to collaborative activities in the case of proposed agreements containing cartel provisions.

Issue 6: Facilitating beneficial collaboration

The Commerce Act recognises that businesses sharing information or collaborating with each other is a feature of well-functioning competitive markets. It provides for this beneficial collaboration through targeted prohibitions and exceptions, such as the ‘collaborative activity’ exception (s 31) and clearance by the Commission for collaborative activities that do not substantially lessen competition (s 65A). If required, authorisation is also available from the Commission on a case-by-case basis if the Commission is satisfied the arrangement has net public benefits (s 58). The application fee for an authorisation is $36,800 (including GST), along with other costs of complying with the Commission’s process. Certain arrangements or conduct may also be specifically authorised by another Act of Parliament or Order in Council (s 43 and s 44). This issue considers if further clarity could be provided under the law to allow for beneficial collaborations and conduct.

Why are we looking at this?

Many of the major structural challenges facing the economy require novel and coordinated solutions. These challenges include transitioning to net zero, technological innovation, infrastructure deficits and geopolitical impacts on supply chains and often have broader public interest objectives (eg national security, geopolitical strategy, development).

The existing provisions and processes in the Commerce Act allow for beneficial collaboration, and the Commission has issued comprehensive guidance. [28] The Commission also has an open door for businesses seeking to sound out any proposals. However, we have heard concerns from some in the business community that the provisions relating to collaborative activities in the Commerce Act are uncertain and Commission processes for businesses to manage the Commerce Act risk can be slow and costly, with the associated risk that beneficial collaboration is deterred. Further, applying for Commission authorisation could be a barrier for some small businesses.

Examples of where competitor collaboration can be beneficial include:

- Collective bargaining by small businesses with large firms with market power.

- Emergency planning or responses.

- Industry arrangements to meet net zero targets.

- Industry-wide collaboration to improve outcomes for consumers, such as addressing financial scams.

Discussion

We are interested in views on the nature and extent of this problem and the merits of possible regulatory or non-regulatory options to improve business certainty.

The cartel provisions in the Commerce Act were amended in 2017 to allow for a wider range of beneficial business collaborations, such as franchises or legitimate joint ventures, where likely competitors can cooperate with other and agree matters that are reasonably necessary for the purpose of the collaborative activity. These collaborative activities must not have an anticompetitive purpose nor substantially lessen competition in a market.

In compliance with these provisions, businesses were able to efficiently and effectively respond during the COVID-19 lockdowns, by pooling resources and coordinating. This is just one example of where collaboration may be permitted if directed at outcomes that benefit the businesses’ customers or suppliers, rather than lessening competition between them.

Businesses can self-assess arrangements, with the benefit of Commission guidance and/or expert legal advice. Certainty will increase over time as the provisions are considered by the Commission and the courts.

If greater certainty is desirable, the table below outlines some high-level options for consideration, but other options are invited.

Options to facilitate beneficial collaboration under the Commerce Act

- Make explicit in the Commerce Act that the Commission has a role in issuing guidance on the interpretation of provisions of the Act, not just dissemination of information about its enforcement approach (s 25). This guidance could be given greater status to assist the courts in interpreting the provisions.

- Empower the Commission, on its own initiative, to issue binding rules that create a safe harbour from the prohibitions.

- Introduce a statutory notification regime for specified classes of arrangements that would operate separate to the Commission’s authorisation process. The effect of notification would be to shift the burden of proof, such that the Commission would have to object to (or call-in) the arrangement if it had concerns on competition or public benefit grounds. If there is no objection, the arrangement would be exempt from specified prohibitions under the Act for a period (e.g. three years).

For example, the ACCC has a notification process for certain classes of collective bargaining arrangements. This includes collective bargaining that involves businesses that expect to make transactions less than $A3 million over 12 months, and excludes trade unions. The fee for notification is $A1,000. - Empower the Commission, on its own initiative, to make class exemptions to authorise classes of conduct that may be exempt from any or all prohibitions in the Act. A class exemption could be subject to terms and conditions set by the Commission. It could cover a range of other issues that have arisen under the Commerce Act where an authorisation is not practical, e.g. agreements on sustainability measures, scams or emergency responses.

For example, the ACCC has issued a class exemption for small businesses to collectively bargain in Australia, which covers businesses with aggregated turnover of less than $A10 million. Groups complete a one-page notice and provide it to the ACCC, and there is no fee for lodging. There have been around 100 industry groups who have lodged notices under this exemption. - Provide an exception for small business from the Commission fee payable to apply for authorisation under the Commerce Act. The power to make regulations under s 108 of the Commerce Act already allows for creating exemptions from the requirement to pay the fee. Under this option, the Commerce Act (Fees) Regulations 1990 could be amended to exempt small businesses from this requirement. However, the parties would still bear the cost burden of satisfying the Commission that the arrangement should be authorised.

Questions for consultation

15. Has uncertainty regarding the application of the Commerce Act deterred arrangements that you consider to be beneficial? Please provide examples.

16. What are your views on whether further clarity could be provided in the Commerce Act to allow for classes of beneficial collaboration without risking breaching the Commerce Act?

17. What are your views on the merits of possible regulatory options outlined in this paper to mitigate this issue?

18. If relevant, what do you consider should be the key design features of your preferred option to facilitate beneficial collaboration?

Issue 7 – Anti-competitive concerted practices

While businesses sharing information and collaborating is a feature of well-functioning competitive markets, there is a point where that collaboration causes harm and becomes anti-competitive collusion. Cartel conduct is the most egregious form of anti-competitive collusion. Cartel conduct is an unjustified interference of market forces that can cause serious economic harm. It is prohibited under the Commerce Act, and since April 2021, intentional cartel conduct is a criminal offence.

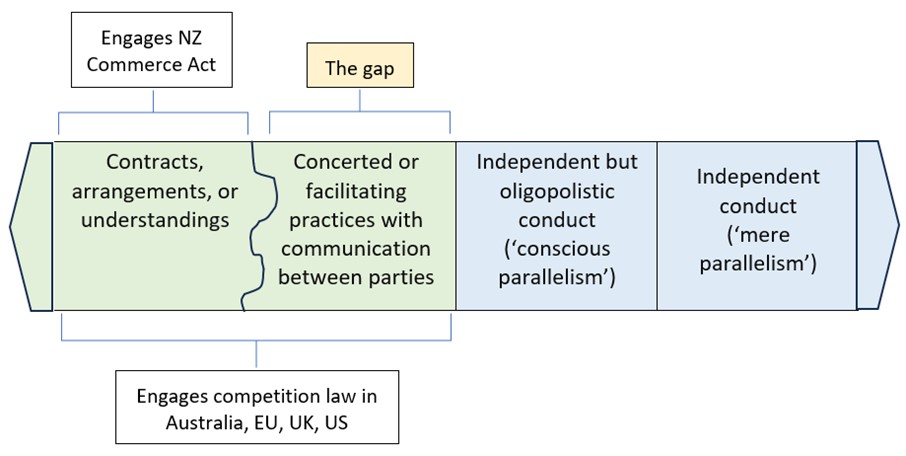

Compared to many comparable overseas jurisdictions (eg Australia, United Kingdom and Europe), there is a further class of harmful coordination that is not currently unlawful under the Commerce Act (which requires evidence of a contract, arrangement or understanding). This ‘gap’ relates to co-ordinated conduct between competitors designed to avoid competition, where the court is unable to conclude that the parties involved had reached an ‘understanding’ about the prices to be charged (cartel conduct under s 30) or reached an ‘understanding’ that the disclosure of information had an anti-competitive purpose or effect (s 27).

An example of such co-ordinated conduct is ‘price signalling’ (where a firm discloses their price intentions to a competitor) that has the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. This could be in a public forum (eg statements made during the earnings calls of public companies or in trade journals) or in a private setting with the competitor.

Why are we looking at this?

New Zealand has many concentrated markets with high barriers to entry. Where these market structures exist, there is a heightened risk of coordinated conduct. An explicit prohibition against anticompetitive concerted practices would ensure the market participants compete on their merits. The case for such a prohibition may be greater given technological advances and increased price transparency, such as through online sales. A generic prohibition of this sort could reduce the need for sector-specific regulation to promote competition.

Discussion

The size of the ‘gap’ in New Zealand competition law for this form of co-ordinated conduct that is harmful is difficult to assess. See figure below.

Diagram representing the 'gap' in New Zealand competition law compared to other countries

New Zealand courts have been willing to infer the existence of an ‘understanding’ [29] from evidence presented and a finding of ‘commitment’ by one or more of the parties to act (or refrain from acting) consistent with a consensus reached between them. [30] Unlike for a ‘contract’, the level of ‘commitment’ necessary for a finding of an ‘understanding’ need not be legally binding.

In addition, mere parallel behaviour where competitors independently respond to external factors, such as cost or demand conditions in a market, should not be condemned by competition law. This includes where competitors are aware of each other’s activities but independently make decisions in response to each other’s pricing and output (ie ‘conscious parallelism’, such as price following behaviour). In such cases, prices may move in parallel, but there is no communication between the parties to co-ordinate.

We have anecdotal evidence of examples where parties have communicated commercially sensitive with each other to limit competition between them. This communication may be direct or indirect, including through intermediaries such as a trade association, supplier or distributor. Examples of this ‘tacit collusion’ include:

- Competitors sending price lists or manuals to each other.

- An industry association collecting commercially sensitive information from its members and publishing price forecasts to assist members in staying in step with the market.

The Australian competition law prohibits ‘concerted practices’ with the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. Concerted practices is not defined, however, the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill which amended the CCA to introduce the concept explains that a ‘concerted practice’ is:

"any form of cooperation between two or more firms (or people) or conduct that would be likely to establish such cooperation, where this conduct substitutes, or would be likely to substitute, cooperation in place of the uncertainty of competition."

The ACCC has issued guidelines on its enforcement approach to the prohibition. [31] It states that a concerted practice involves replacing or reducing competitive, independent decision-making with cooperation with competitors, such as by communicating and exchanging strategic commercial information. If a party inadvertently receives commercially sensitive information from a competitor, they should take immediate steps to make clear that they do not wish to receive or act upon that information.

Since the concerted practices prohibition was introduced in 2018, the ACCC has had one enforcement action. In November 2022, Lawn Solutions Australia Group Pty Ltd provided a court-enforceable undertaking to address ACCC concerns that it may have engaged in a concerted practice. The turf breeder company was circulating price surveys with requests that growers and resellers set their prices in line with its recommended prices. It also put pressure on individual growers and resellers to increase prices if they sold turf at a price below that recommended.

Some commentators have suggested alternatives to the ‘concerted practices’ prohibition to increase business certainty. This includes targeting the prohibition to focus on coordination between would-be competitors only, considering the purpose of the conduct, and whether it has likely effect of substantially lessening competition between the parties. [32]

Others have noted that the prohibition is only a partial solution to the emerging challenge of algorithmic collusion on pricing. If algorithms are used to facilitate communication and enforcement of coordination strategies, then that conduct may engage the prohibition. However, if the algorithms are used to unilaterally set prices or market strategies based on the actions of other market participants (but with no communication between the parties), this conduct is unlikely to be caught despite raising the risk of significant harm to consumers. [33]

We are considering the following options, along with any options suggested by submitters:

- Status quo – Maintain the generic prohibitions requiring evidence of a ‘contract, arrangement or understanding’ to establish anticompetitive collusion.

- Align with the Australian prohibition to explicitly prohibit concerted practices that substantially lessen competition – This would address the ‘gap’ in our competition law in dealing with tacit collusion in concentrated markets. Only practices that substantially lessen competition would engage the provision. This option would further align with Australia’s competition law to promote business certainty.

- Adopt a customised prohibition focused on the conduct that facilitates coordination – A new prohibition could target the anti-competitive conduct that arises from harmful forms of tacit collusion, such as sharing of commercially-sensitive information without appropriate safeguards. However, this would require careful wording to ensure it did not deter pro-competitive forms of collaboration, as there can sometimes be legitimate reasons for competitors to exchange commercially sensitive information (eg as part of due diligence of potential acquisitions).

Questions for consultation

19. What are your views on whether the Commerce Act adequately deters forms of ‘tacit collusion’ between firms that is designed to lessen competition between them?

20. Should ‘concerted practices’ (eg, when firms coordinate with each other with the purpose or effect of harming competition) be explicitly prohibited? What would be the best way to do this?

Footnotes

[28] Competitor Collaboration Guidelines (January 2018) [PDF, 1.9MB](external link) — Commerce Commission

Collaboration and sustainability guidelines (November 2023)(external link) — Commerce Commission

[29] Or arrangement

[30] Lodge Real Estate Ltd v Commerce Commission [2020] NZSC 25, (2020) 15 TCLR 553

[31] Guidelines on concerted practices (2018)(external link) — ACCC

[32] Beaton-Wells, Caron, and Brent Fisse (May 2015), Submission on the Final Report of the Competition Policy Review (Harper Review), 22 May 2015 [PDF, 116KB](external link) — Brent Fisse Lawyers

[33] AI Price Wars: Algorithmic collusion or competition ‘at speed’?(external link) — Gilbert + Tobin Lawyers

< Chapter 2: Mergers | Chapter 4: Code or rule-making powers and other matters >