Introduction

On this page I tēnei whārangi

Increasing the supply of housing is a top priority for the Government. One way to support this is to make the building consent system faster, easier, and cheaper to use.

Housing affordability is a key issue Aotearoa in New Zealand

Aotearoa New Zealand has some of the least affordable housing in the world[1]. Home ownership dropped from 74% in the 1990s to 65% in 2018[2]. Over the 12 months to June 2023, average housing costs per week increased 14.5%. Data from 2023 illustrates that over a quarter of households that do not own their home now spend more than 40% of their income on housing[3].

Regulatory barriers increase the time and cost to build new houses

Building costs are high and have cumulatively risen 41.3% since 2019[4]; it is about 50% more expensive per square metre to build a standalone house in Aotearoa New Zealand than in Australia[5].

It can take a long time for a house to be built and receive a code compliance certificate. Homes consented in the June 2022 quarter took, on average, over 16 months to reach final inspection (up from 14 months in the June 2021 quarter) and a further two months to receive a code compliance certificate[6].

Poor coordination and sequencing of trades on-site has a significant impact on build times and increases the risk of defects (which can add more time due to the need for rework). Added to this are regulatory delays including processing minor (or major) variations and, delays waiting for inspections.

These delays increase the cost of a build project and reduce the sector’s capacity to supply affordable housing.

Work underway to improve the building consent system

The inspection process is only part of the overall time it takes to build and there are wider opportunities to make the sector more productive. Table 1 below sets out the work MBIE is doing to improve the consent system and make it easier and cheaper to build.

Programme of work to streamline the building consent system

- Public consultation on increasing the uptake of remote inspections (this discussion document)

- Regulations to clarify the definition of ‘minor variation’ to make substituting products more predictable and consistent

- Defining ‘minor customisation’ for MultiProof to allow minor design changes without voiding a certificate

- Removing regulatory barriers for using overseas building products and requiring councils to accept products that meet international standards

- Public consultation on making it easier to build ‘granny flats’ up to 60 square metres

- Recognising producer statements to reduce the amount of checking that building consent authorities need to do

- Requiring councils to submit data on timelines for building consents and code compliance certificates every quarter, which is published on MBIE’s website

- Changes to Building (Accreditation of Building Consent Authorities) Regulations 2006 to enable more time to focus on consenting, inspecting, and code compliance certificates (commenced June 2024)

Work to identify the best way to deliver consenting services could lead to changes in the building work that needs to be inspected and who does those inspections. As potential changes could be significant, it will take time for decisions to be consulted on and made, and for changes to take effect.

It is important that we continue in parallel to progress work to make it easier, cheaper and faster to build. It is likely that remote inspections will play a key role in the future delivery of consenting services.

We are keen to hear your views on the short- and long-term costs of the different options for increasing the uptake of remote inspections. We will consider the implications of potential changes to the delivery of consenting services prior to seeking final policy decisions on remote inspections. This could include focussing on options to improve efficiency under the current structure that would also be compatible with any future model.

Outcomes and criteria

The primary objective of the options in this discussion is to improve the efficiency and timeliness of building inspection processes to make it easier, cheaper, and faster to build.

We also understand the importance of balancing regulation with the need to facilitate a productive building and construction sector and ensuring that changes do not have a detrimental effect on the quality of Aotearoa New Zealand’s housing and building stock.

The primary focus of the building control system is ensuring buildings are healthy, safe and durable, and that buildings are built right the first time.

We want the system to be agile and responsive to changes in the way New Zealanders build while also avoiding defects and building failure that can be stressful and costly to address. To this end, government intervention in the building consent system should seek to achieve the four outcomes described below:

- System is efficient: the implementation costs of option(s) are minimised to ensure costs do not outweigh the benefits.

- Roles and responsibilities are clear: the option(s) do not make the system more complex and ensure that liability falls on those best able to identify and manage risk.

- Requirements and decisions are robust: the option(s) do not increase the risk of defects.

- System is responsive to change: the option(s) allow for flexibility and innovation in how parties comply and improve the ability of the system to respond and adapt, including to any future system.

We want to implement the best option(s). The best options will be those that achieve the greatest reduction in cost and time to build, and greatest improvement in ease of building, while meeting the four system outcomes.

Question 1: Do you agree these are the right outcomes/criteria to evaluate the options? Are there any others that should be considered?

Legislative context

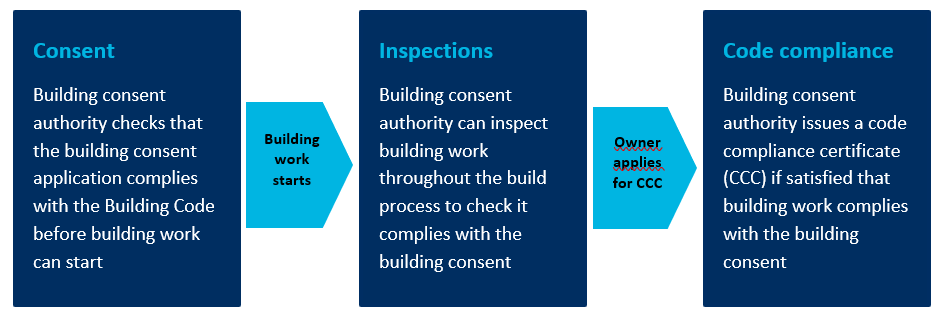

The Building Act 2004 (the Building Act) is the primary legislation governing the building industry in Aotearoa New Zealand and provides the framework for the building consent process, which is outlined in the diagram below. These steps add time and cost, but they give building owners, tenants, banks, and insurers confidence in the quality of the building work.

Diagram description

Footnotes

[1] OECD (2020) How's Life? 2020: Measuring well-being. OECD publishing, Paris

[2] Statistics New Zealand (2020) Census data from Housing in Aotearoa

[3] Statistics New Zealand (2023) Household income and housing-cost statistics: Year ended June 2023(external link)

[4] This represents the cumulative increase since quarter 4. This mostly occurred in 2021 and 2022

[5] The average cost per square metre to build in New Zealand includes demolition costs and 15% GST, whereas the Australian figures exclude demolition costs and includes 10% GST

[6] Experimental indicators show longer building timeframes – Statistics New Zealand(external link)